|

I woke up today and began my weekend-morning routine. I grabbed my happily blabbering daughter from her crib, poured a steaming mug of coffee and sat on the balcony to listen to the birds. And Alanna's desperate attempts to converse with the neighborhood dogs. It struck me that I only have a few more days to enjoy this – after four years, we leave Paraguay for good in just three weeks.

This sparked a reflection on the lack of blog-posts I’ve written about Paraguay. My occasional writings mostly reflect the travelling we’ve done outside of Asuncion and rarely explore our daily experiences here. Over the next few weeks, as we prepare for our exit, I’ll be posting several pieces about things I’ll miss about Paraguayan life, about things I won't miss and memorable episodes from the last four years. Hopefully these bittersweet musings will help me recall interesting experiences and will prove interesting reading for Alanna in the years to come. Thanks for reading.

1 Comment

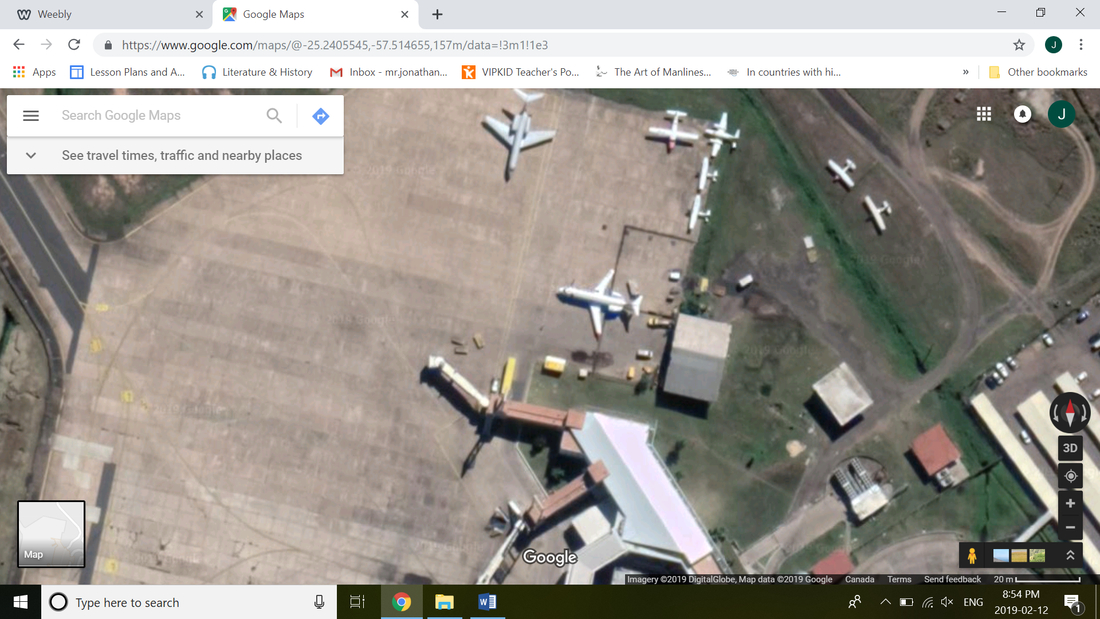

Every time I depart the Silvio Pettirossi International Airport in Asuncion, I am confronted, haunted even, by a rich mystery: why is a lonely biohazard container sitting on the edge of the tarmac? This vibrantly yellow container screams, by design, to “keep me away from people!” Yet, the hulk of neon metal has inhabited the fringes of the airport for at least four years: I noticed it the first time we departed from the ASU airport in 2014! I don’t have a whole lot of concrete information to share about this enigmatic container. I’ve Google-searched it, talked to students whose parents’ own hangers and even asked a ticket agent, all to no avail. The best I can offer is to share some of the questions I have regarding this mysterious hunk of corrugated metal:

That’s about all! I was raised in Eastern Canada, where faint flashes on the horizon and distant rumbling counted as “thunder and lightning.” The excited chatter that ensued in elementary school on those rare occasions is, in retrospect, cute. I almost laugh at how excited I could become at the sight of a few silent streaks of lightning out at sea.

The earliest “real” thunderstorms I can recall were in Alabama on our regular summer vacations to visit family. I remember standing barefoot on the concrete pad outside Grandma’s laundry room as a child, sheltered under the awning of the roof and peering at the yard obscured by a sheeting curtain of rain that poured from the gutters. The rain was so thick you could barely see the other end of the yard. You could feel the thunder reverberate in your stomach! For a Canadian kid used to quiet snowfall and foggy rain, these deluges seemed Biblical in their intensity. They were invigorating and exciting like no snowstorm or rain-shower back home in Nova Scotia could ever compete with! I loved thunderstorms when I lived in Bangladesh for two years as well. I would regularly stand by our back window watching as lightning, appearing in faint colors of blue, yellow and green due to the heavy air-pollution, struck buildings and trees off in the distance. I’d often use the din of thunder and rain to cover up my amateur guitar playing and vocal accompaniment. Once, a thunderstorm hit our neighborhood so hard that there was a literal waterfall running down the apartment building’s stairs from the roof. Even though our apartment risked flooding from above, a situation that felt so paradoxical, I still had an eager smile plastered across my face for the whole episode! Now, in Paraguay, thunderstorm-season is beginning anew, and I realize how much I’ve missed the random, lightning-filled deluges that characterize this corner of the world. As I write this, I’m sitting on our balcony. The thermometer reads 36 degrees and the wind has been mounting all day. A tangible energy dominates. The air is electric. Every inch of my body seems to tingle. When I breathe the humid, earthy taste of Paraguay, my mouth salivates. Birds flap their wings as they return to their nests, calling one another in a manner that seems to communicate urgency. The street-dogs below are barking. The odd person or car that bustles past is clearly hoping to avoid being caught in the downpour and ankle-deep floods that could ensue. The tension mounts… Intermission: I spend thirty minutes feeding my blue-eyed baby girl blended chicken and butternut squash. She doesn’t want to eat. I discover that, if I jiggle my belly enthusiastically or contort my face until it hurts, she will approve the meal and agree to take a single bite. Dance. Clown. Repeat. Dance. Clown. Repeat. End of Intermission: Back to thunderstorms! Lightning is flashing through the clouds now and the temperature has dropped at least ten degrees. The air is fresh and cool in comparison to the heavy, swamp-butt humidity that dominated all day. Now, as I sit tucked into the nook of my balcony that splatters the least rain on my laptop, I watch the storm unfold. The rain sheets past the streetlight below looking like shimmering silver tinsel on a Christmas tree. The trees bend and whip frantically in the wind. The smell of rain fills my nostrils as bright flashes of light illuminate a leaden sky and thunder cracks all around our apartment building, assaulting me from different angles. I feel alive! I think that electric feeling of life is one of the reasons I exhibit a childlike excitement when each thunderstorm rolls in. The intensity and energy of each storm reminds me that life isn’t all dishes, diapers and paperwork-drudgery. It is filled with wonders too. Thunderstorms are my occasional reminder to marvel and wonder at some of the beautiful sights, sounds and smells of Paraguay. Danielle, I think, secretly enjoys my rush to the designated spot on the balcony with the signs of an impending squall. My thunderstorm giddiness is largely hidden in public. Most of you (I now directly address the very few people who read this) will never see that side of me. But rest assured, whenever a storm rolls in accompanied by rain, lightening, wind and thunder, the bare-foot boy who was entranced by those Alabama-downpours emerges. I hope he will never go away. I don’t often focus on current-events with this blog, as it is designed to be a (rarely updated) record of our experiences abroad rather than a soapbox for political rants. With the recent events in Charlottesville, Virginia raging through my mind, I’ve been reminded of Paraguay’s recent struggles for reconciliation after a dictatorship and thought that it offers a few interesting parallels.

Alfredo Stroessner’s 35-year rule of Paraguay earned him the dubious distinction of being the longest-ruling dictator in the South America. He was devoutly anti-communist and used harsh methods of intimidation, torture and murder to maintain his iron-grip of the country. His legacy in Paraguay continues to be controversial today. Many of Stroessner’s former supporters maintain political and economic control as members of a business-elite; they revere him and openly pine with nostalgia for the good ole days of his totalitarian dictatorship. Most of the intellectual class in contrast, as the primary victims of Stroessner’s suppression campaigns, hate everything he stands for with a vehemence that is astounding to witness in person. Paraguayans are known for being a relaxed nation; the national motto is tranquilo pa, which loosely translates to, “no worries.” But emotions can run hot when Paraguayans discuss Stroessner! That’s where the connection to Charlottesville came to mind. Stroessner (like most dictators it seems) had a statue fetish. The country was covered with bronze effigies of himself standing authoritatively, confident in his total control. When he was ousted in 1989, congress passed a law mandating the removal of all statues from plazas, hills and roadsides around the country. They also demanded the renaming of schools, roads, buildings and anything else bearing his name. Even the second largest city in the country, Puerto Stroessner, was rechristened Ciudad del Este. This task was monumental (pun intended). It took two years but in 1991, a final one-ton statue was removed from a hill-top in Lambare. What the Paraguayans did with the scrap in 1991 could, in my opinion, serve as an interesting compromise for the Southern United States’ plethora of Confederate statues. To remember the legacy of Stroessner, the innovative Paraguayans dismembered the statue and smashed it between two blocks of concrete. They then set it up again in its mangled form in a downtown Asuncion plaza, where it still sits today. I feel like this balances the arguments on both sides of the debate, the “preserve our history” crowd and the “tear it down” protester camp. When I first noticed the memorial during my second trip to the downtown core after I’d moved to Paraguay, I had a surprisingly visceral reaction. To me, Stroessner’s face peering out of the concrete, his hands reaching as if he is caged, seems like a huge political statement; although Paraguay may never fully escape from his shadow, that doesn’t preclude a newfound commitment to justice and democracy. I think this is my favorite Paraguayan monument as a result. Thanks for reading my musings. The first time I heard of Paraguay was in tenth-grade history class. After being assigned the task of researching preventable disasters and exploring strategies for avoiding similar tragedies in the future, one classmate presented on a little-known corner of the world: Asunción. A fire in a supermarket had killed almost four-hundred people, largely because there were few fire-exits incorporated in the design and, at the outset of the fire, the front doors had been locked by a security guard to prevent theft. After discussing the horrifying case with my class for a few minutes, I promptly forgot about the blaze; Paraguay’s largest peace-time disaster was relegated to the deep recesses of my memory. Then I moved to Asuncion. Within a few weeks of arriving, the local newspapers filled with stories and features highlighting the tenth anniversary of the tragedy. I learned about the victim’s families’ search for justice and the ensuing court cases that led to the imprisonment of the supermarket’s owners, a security guard, the architect and some minor municipal officials. Protestors ten years later still felt cheated by the light sentences handed to those responsible. The papers were packed with photos and charts outlining the blaze itself and the derelict building as it now stands – a hulking, burnt-out testament to hundreds of lives gone up in smoke. I’ve wanted to visit the ruins of Ycuá Boleños since I first drove past it during our first week in Paraguay. My penchant for wandering through abandoned places has been strong since my early teens (and has, coincidentally, gotten me in trouble on a few occasions) but, seeing as how visiting the wreckage of a horrifying disaster hardly qualifies as a romantic date with my beautiful wife, the adventure never materialized. Until this week. Paragraph. Haz clic parked my car a block away from the building and walked straight through what used to be the main entrance. There is a barred-off memorial with grainy photos of the victims, weather-worn personal belongings and droopy plastic flowers that is inaccessible except, perhaps, on special occasions. I passed a simple metal plaque containing the names of all 396 victims plastered onto the brick façade as I climbed the broken stairs up to the main level. Apart from several homeless natives and a small band of super-sketchy young men sporting haunting facial tattoos[1], I had the place to myself. It was odd how normal the place felt – no different than any other abandoned building I have visited in the past. I think I was expecting some sort of indefinable, creepy vibe but I didn’t find it there. As I wandered through the offices where the order came to close the doors, skirted past what used to be the food court where the fire began, explored the carniceria where dozens sought refuge in meat-refrigerators in a vain hope that the cooler temperatures would help them, I couldn’t help but think, “Why am I here?” I started thinking. Occasionally, when I start thinking, I stop having fun. That was the case here. I left when I began honestly considering my motivations for going; I wasn’t paying my silent respects at a memorial. I felt more like a voyeur, peeking in on something I could never be a part of and never fully understand. I was reminded of visiting the cremation pyres in Kathmandu, Nepal and I remembered the unique smell of burning flesh. It was time to leave. As I left the abandoned supermarket-shell, I felt guilty in a way that I still can’t explain. I’m still trying to answer the question for why I went, and why others go, to monuments of unspeakable horror like Ycuá Boleños. What compels humans to visit the sites of mass human suffering? How closely should I examine my motivations for exploring these kinds of places?

Although I’m glad I went, in a way, visiting the wreckage of the Ycuá Boleños supermarket made me supremely uncomfortable with myself. It will be filed away with other experiences I’ve had internationally where my thoughtless moral assumptions and motivations have been challenged unexpectedly. It is often these experiences that result in the most learning over time though…hopefully I’ve learned yet another indefinable lesson with this one. [1] I openly admit that I became frightened when two of these (probably hardened gang-members) dudes started following me around the complex. I tried to avoid them and head for the exit but they cut me off and walked up to me. The following stream-of-consciousness monologue is an attempt to summarize my thoughts as they strolled towards me: “Damnit Jon, what have you done? Why do you always put yourself in these dumb situations? You’ve never been robbed when Danielle is around…the problem is obviously you doing stupid things! They’re coming closer. They are coming for me. No doubt about it! The dude on the right tattooed his whole face in to look like a skull…does that mean he kills people? I hope he can’t hear my heart beating. He’s putting his hand in his pocket!!! I hope he’s the type to ask for my phone rather than shoot and then take my phone. Oh, Lord, I hope this is quick. Wait, he’s still empty handed. He’s reaching out his hand and…. asking where I’m from and smiling?!? He hopes that I like Paraguay? He hopes I have a good day? Well that was an overreaction!” I continue to be surprised by Paraguayan hospitality and friendliness…even from the ones who, if you adhere to the stereotypes, look like they would murder you without a second thought! |